“THERE IS ONLY ONE THING IN THE WORLD I AM AFRAID OF…IT’S A LIGHTED MATCH”

Life and work in Chicago during the early days of the 20th century meant a day to day adventure through a wild and wooly metropolis.

Surrounded by the din and dust of industrial factories, streets crowded by thousands of workers, and a spider web of electrical wires that tended to inspire a weekly barrage of building fires, The Reilly & Britton Company made a decision in 1912 to get out.

Relocating in May of that year to a quiet spot on Michigan Boulevard, where Grant Park and Lake Michigan kissed, must have seemed a luxurious – and bold – move to rivals in the publishing industry. But Reilly & Britton, started only a decade before had, like the city of Chicago itself, grown to surprising success. A success due mostly to the outstanding sales of a single author – L. Frank Baum.

Settling into a new office, which occupied the entire 19,000 square foot fifth floor at the Graphic Arts Building, was a chance for the company to both consolidate its efforts, and expand its reach into limitless potential in what seemed to be an idyllic environment.

A pair of newspaper advertisements, recently rediscovered by author, Michael Patrick Hearn, however, speak to an event (or perhaps even a series of events) that occurred scarcely a year into their new residence that must have rattled that confidence.

A sale list posted by the Emporium Department Store in The San Francisco Chronicle on Sunday, February 8, 1914 announces that 3,000 juvenile books published by Reilly & Britton will be offered at cut prices after being water damaged due to a fire in an adjoining building. An ad a year later in The Washington Post offers similarly “spotted” lots of stock “suffered a loss through the unexpected release of [Reilly & Britton’s] sprinkling system.”

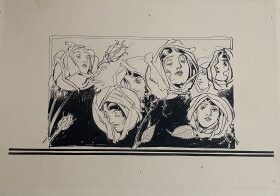

In The Lost Art of Oz search, one of the central mysteries is the missing artwork for early Baum titles like Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz, John Dough and the Cherub, and Sky Island. Indeed, some of illustrator, John R. Neill’s most sumptuous efforts were drawn pre-1914, but are unaccounted for.

Along with book stock, could original series artwork have been badly damaged in the event mentioned in these clippings?

Not knowing how the artwork was stored in the firm’s offices, it does seem possible. And no doubt, if badly damaged by water or smoke, artwork which was drawn on illustration board in pen and ink or painted in watercolor might simply have been discarded. On the other hand, artwork from other early Reilly & Britton titles, like The Marvelous Land of Oz, Ozma of Oz, and The Road to Oz is known to survive, and none of it appears to have suffered any related fire or water damage.

For now the evidence remains inconclusive. But the ads do provide an interesting speculative footnote into Oz archival history.

Special thanks to Michael Patrick Hearn and Atticus Gannaway for providing materials and expert opinion for this article.